What can be said about Mauvais cœur—the text, that is—without resorting to paraphrase? It needs to be referred to in the same roundabout way in which it is written. Its mystery is as complete as it has always been. But why is it that so many readers, with different lives and from different backgrounds, feel similarly implicated in its meanderings and affected by this primitive scene, this fragment of existence; and why, while affirming that they have never experienced anything of the sort, do they admit to having felt, amongst the trees of such an autumnal garden, the same inexplicable distress?

Fargue, in Mauvais cœur, is neither the acrobat of Ludions, of which Satie was so fond, nor the indefatigable “pedestrian of Paris”. He is the (possibly lesser-known) man, who at the age of thirty, in a collection of prose pieces bewitching enough to justify his title, Poëmes, resumes his life in a handful of sentences, limits it straight away to a few painful images. Thirty is young, early, to have shut oneself so definitely, and irremediably, in the past, leaving the present time—to say nothing of the future—virtually no chance at all, granting it only the possibility of regret, the consolation of memory.

By the time I was thirty, I too had already shut out the future. Mauvais cœur is akin to my Chansons enfantines and my first Poésies de Georges Schehadé, in which I tried to give my voice, my path, an illusory duration within the only time I really know how to experience. The more I move away from childhood, the more I feel its strength. This is not a paradox: the child is fragile, yet childhood is as hard and as enduring as a diamond.

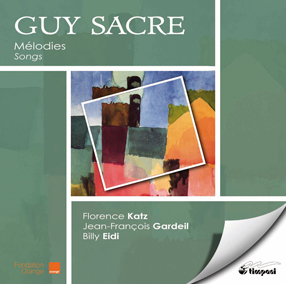

Guy Sacre

(translation John Mary Pardoe)

Extraits sonores

Mauvais cœur

Nomenclature

baryton et piano