Oldham’s setting of the Laudes creaturarum was composed in 1961 as a result of a commission from the Spode Music Week, a festival with workshops, founded in 1954 and still in existence. During those weeks of music, amateur and professional musicians come together, not only for concerts and lectures, but also for daily church services, which provide an opportunity to hear some of the great works of the choral repertoire.

The text Oldham chose for this work must have had a particular resonance for him. For, after a difficult childhood, an unsettled adolescence and an unproductive period of several years, his conversion to Catholicism in the mid-1950s marked the beginning of an important stage of his life, in which his main interest was choral music, particularly as a choirmaster, but also as a composer. In 1956, he was appointed conductor of the choir of St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh and, with those singers, explored the treasures of sacred music.

The poem, written by St Francis in about 1225, is a hymn of thanksgiving that recalls Psalm 148 and the Beatitudes of Matthew the Evangelist. The heavenly bodies (the sun, the moon, the stars), the elements (air, water, fire, earth), men of goodwill (the merciful, the meek, the peacemakers) and, finally, death are successively the object of the praise offered up to the “Most High, All Powerful and Good Lord”.

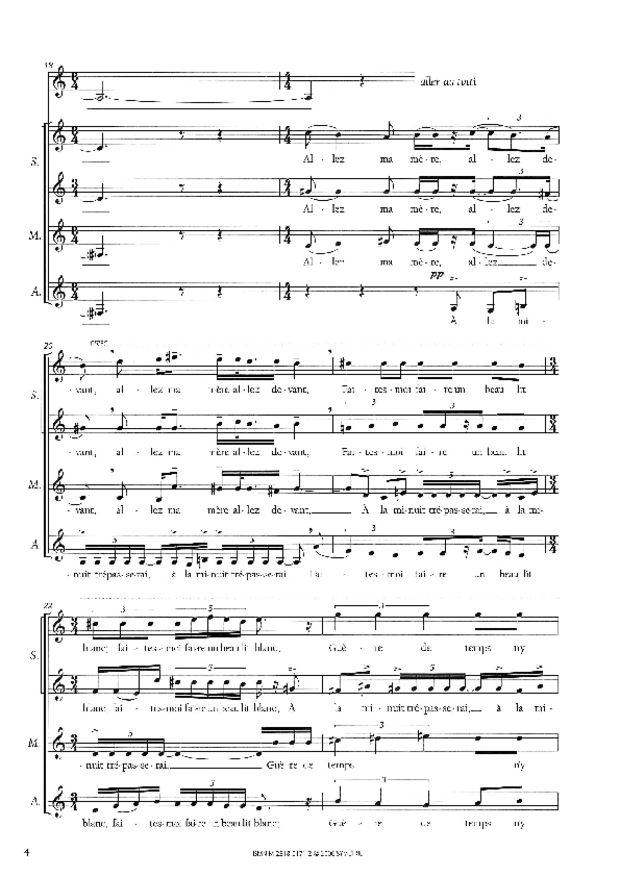

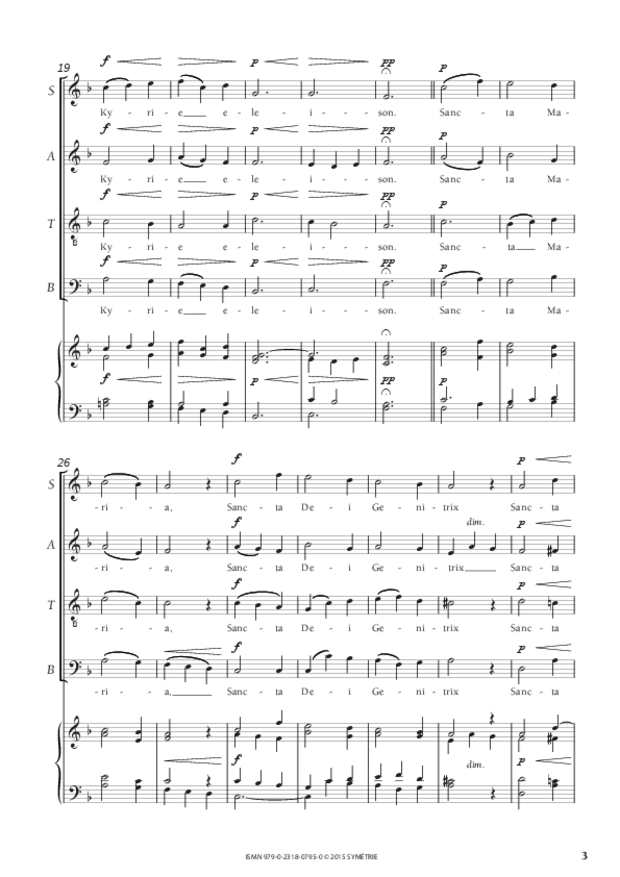

Oldham keeps to the original language, Umbrian, and follows the overall structure of the text, so that the piece is cast in ten short and strongly contrasted sections. The modal writing plunges us into a mysterious mediæval world. The mastery of choral writing in this work, in which Oldham both alludes to early musical forms, without slavishly imitating them, and also borrows from the melodic motifs of popular music, was without doubt the fruit of his long collaboration with Benjamin Britten. The forces required for the work, as well as certain orchestral and choral textures, cannot but remind us of the Saint Nicolas cantata of his illustrious teacher.

Like his predecessors in the English choral tradition, Oldham was a pragmatic composer. His training and experience, as percussionist, composer of ballets, orchestral conductor, made him the complete craftsman. Although his musical language was essentially tonal, he was always open to influences from those of his contemporaries who had explored other ways of writing. As a performer himself, his control over the technical difficulties of his works is never at the expense of their artistic intentions. His proficiency in the art of composition, particularly for voices, had its origin in the studies under Herbert Howells, but it was his association with Benjamin Britten that made him aware of the primacy of personal inspiration. In a style that is classical without being conventional, the poetry of the musical discourse holds sway.

We know Arthur Oldham as a conductor of choral music, but have yet to discover him fully as a talented composer. Let us hope that this edition of Laudes creaturarum will contribute to that discovery.

Lionel Sow

(translation Michael Bulley)

Nomenclature

soprano solo, chœur de filles, chœur mixte, cordes et orgue

All available forms

-

sheet music pour soprano solo, chœurs, cordes et orgue

-

conducteur et matériel

soprano solo, chœur de filles, chœur mixte, cordes et orgue · 25 min · 21 x 29.7 cm · stapled booklet · ISMN 979-0-2318-0825-4

Publisher : Symétrie

on hire

-

réduction pour voix et piano

46 pages · ISMN 979-0-2318-0826-1 · minimum order quantity: 20

Publisher : Symétrie

Price : €25.00

-

conducteur

20 min · 47 pages · ISMN 979-0-2318-0824-7

Publisher : Symétrie

Price : €52.00

-

-

sheet music pour soprano solo, chœur de filles et clavier

-

soprano solo, chœur de filles et clavier · 5 min · 21 x 29.7 cm · stapled booklet · 12 pages · ISMN 979-0-2318-0831-5 · minimum order quantity: 20

Publisher : Symétrie

Price : €12.00

-