This edition of the work entitled Mesure composée [Combined Metre], written probably in the mid-1790s, is based on the manuscripts Ms 12079 and 2496 of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The latter is a collection, with the title Practische Beispiele [Practical Examples], of 24 pieces for piano with explanatory text, of which Mesure composée is No. 3.

This work was written at a time when Reicha was experimenting with new compositional ideas. The Practische Beispiele includes, for example, a fantasy that uses only the three notes of the triad of E major, another piece written on three staves each with a different time signature, as well as two pieces, Nos. 6 and 12, in which 12 of the black keys are to be tuned a semitone lower, thus allowing a new method of repeating or superimposing the same note. In No. 12, the lower stave is written in F major and the upper stave, containing the modified notes, with a key signature of five sharps, just as for B major or G sharp minor, but producing, in reality, only the notes of the scale of C major.

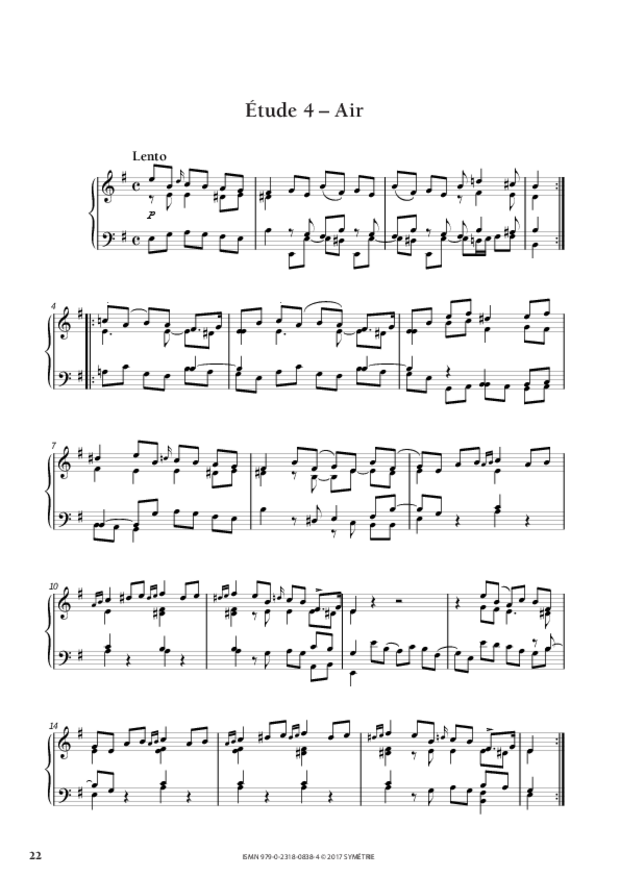

Mesure composée belongs to these experiments. The work is written entirely in 5/8, a metre of which very few examples are to be found among other composers of the period. Reicha, however, employs it also in the third fantaisie of Harmonie for piano, for example, as in the finale of the string quartet entitled Quatuor scientifique, and in No. 20 of his 36 Fugues. In his preface to that work, Reicha explains that a metrical basis of five is quite normal in folk music. Aware that most pianists would be unfamiliar with this rhythm, he adds an explanatory page in the Ms 12079, rewriting the first four bars of Mesure composée as eight bars in pairs of 3/8 + 2/8. In his commentary on this work, Reicha makes a passionate defence of the new metre. He writes:

“Quintuple metre, which may be specified more precisely as a complex time signature such as 3/8 + 2/8, has the same claim on our feelings as the metres of 2/4, 3/4 or 6/8. It is quite as able as them to describe and depict those affects only music can express. It is, though, rarely employed, and that is why we find it foreign. We must, then, make ourselves used to it. If you are to appreciate it, you must get to know it and not hold its strangeness against it.”

He continues:

“Let no one think, either, that composing in 5/8 time has required greater effort from me than with conventional metres. In fact, I became used to it very quickly, and my daily exercises with it have likewise convinced me that its use could easily become widespread, if the weight of prejudice against it were no longer there.”

Press reviews

Over a hundred of Reicha’s compositions have been published and a great number still remain in manuscript, among which many are of the highest importance to the art of music.

Hector Berlioz, Journal des Débats, 3 July 1836