To each of us, Supervielle can effortlessly speak ‘his sweet native tongue’. This is not necessarily the criterion for ‘high-wrap’ poetry, and Mallarmé would be there to tell us the exact opposite. But it is that of an everyday poetry, peaceful and reassuring, present in and faithful to all stages in our life, capable of taming our frights and sorrows, intensifying our joys, and, in its best moments, revealing the secret of a human-scaled fantasy. Attesting to this are his renewed bestiaries, his naive cosmology, his soulful botany, and his humour devoid of spite or ulterior motives. One can certainly associate with Supervielle the lovely phrase Borges used to describe Verlaine: ‘innocent like birds’.

For a musician, Supervielle is, just as much as Verlaine, an inexhaustible treasure. Everything, or nearly, sings spontaneously, prodigally, in these poems, which are so fluid and shifting. Verlaine’s art of the verse is admittedly more considerable (I speak of Verlaine’s first period, which ended with Sagesse), surer and also more sly, skilled at playing all the subterfuges of meter and rhythm. There is not the shadow of a procedure with Supervielle, for whom ‘writing’ is especially not ‘composing’. In ‘composing’, it is the prefix that is at fault for what it suggests of assembly, combination, and resorting to various tools, the use of which we learn from Banville. With Supervielle, one more frequently hears the nursery rhyme than the poem: that is probably what held my attention in these texts – in addition to the themes of age, of a time impervious to pain, and childhood lost forever.

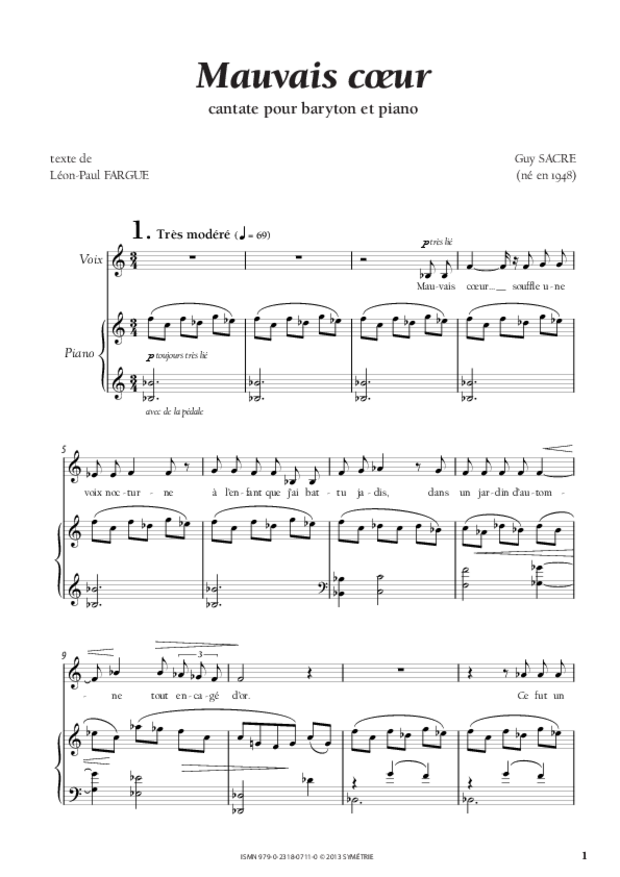

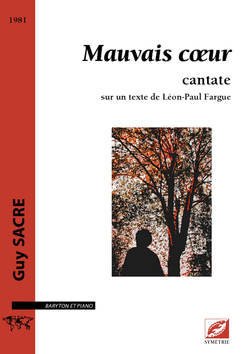

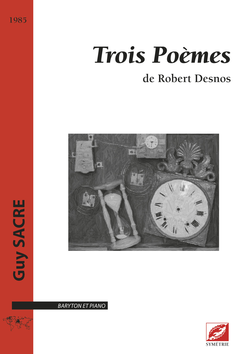

Guy Sacre

(translation: John Tyler Tuttle)

Sommaire

L’Âge

Prairie

Matinale